House renovations are just house renovations. However, sociologists, historians, and other social scientists show how something as innocuous or even positive as house renovations can have very different meanings or contradictory meanings in different time periods.

House renovations are just house renovations. However, sociologists, historians, and other social scientists show how something as innocuous or even positive as house renovations can have very different meanings or contradictory meanings in different time periods.Sociologists often look at visual culture to understand the meaning of social phenomenon, like house renovation. Here is a Post article from November 25, 1965 (p. H1) that I saw in the papers of the Capitol Hill Restoration Society (CHRS) in the GWU Special Collections Research Center. Since this article was saved for decades and was the only item in its folder, we can be assured that it had some importance to the person who saved it.

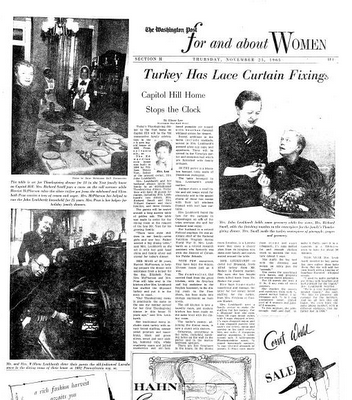

This newspaper article is about the Thanksgiving dinner being prepared by Mrs. John Leukhardt at her long-time family home, the Yost house at 1002 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE. From the CHRS documents, I have noticed that the Yost house was mentioned quite a lot and thus had some importance to the CHRS. Just glancing at the article, we can see that it is addressed to women, since it is in the section "for and about Women" and ads for women's consumer items, like the Corset World ad in the lower right-hand corner. Also, we can see in the caption of the right-hand photo that women do not have their own names: "Mrs. John Leukhardt" and "Mrs. Richard Small." Next, the article's sub-title is "Capitol Hill Home Stops the Clock." Taking this seriously, we can ask, why would someone in 1965 want to stop the clock? Or is there a desire to, in fact, go back to an earlier time?

Throughout the article, the author demonstrates great concern with stopping time:

"Our Thanksgiving menu is practically the same as the one my mother served for her first Thanksgiving dinner in this house 71 years ago," said Mrs. Leukhardt.Maybe the article's author and the woman interviewed in the article want to return back to 1904 or 1894 when the house was built? It is difficult to tell exactly when they might want the clock to stop. There were some changes, such as a "modern kitchen" and lace recently acquired from a trip to Copenhagen, but "Otherwise, everything is the same." Therefore, some changes are accepted and others are not. What might be unacceptable changes?

"With few exceptions, they have kept the 4-story 12-room house just as it was."

"We're a very traditionally-minded family," she said. "We like to preserve old customs for the holidays. And we all love this old house. We even have the same phone number with a different exchange, that my father had in 1904."

Sociologists often look for unspoken or invisible aspects, which are obvious now. F

or example, the two women in maid's outfits in this photo have their own names, Harriet McPherson and Elizabeth Prue, and are taking over the cooking of dinner once Mrs. Leukhardt has stuffed the turkey and put in the oven. The article says that Mrs. Leukhardt "mashes the sweets and combines them," but it seems likely that the women in maid's outfits are doing this work. The Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Could this article be expressing concerns about women and African Americans not "knowing their place" anymore? Might a claim to be "very traditionally-minded" be a claim against social movements for women and African Americans. Does this article show some underlying connection in people's minds in the past among house preservation/renovation, stopping the clock or turning back the clock, and anti-civil rights?

or example, the two women in maid's outfits in this photo have their own names, Harriet McPherson and Elizabeth Prue, and are taking over the cooking of dinner once Mrs. Leukhardt has stuffed the turkey and put in the oven. The article says that Mrs. Leukhardt "mashes the sweets and combines them," but it seems likely that the women in maid's outfits are doing this work. The Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Could this article be expressing concerns about women and African Americans not "knowing their place" anymore? Might a claim to be "very traditionally-minded" be a claim against social movements for women and African Americans. Does this article show some underlying connection in people's minds in the past among house preservation/renovation, stopping the clock or turning back the clock, and anti-civil rights?

Just a note about an oft-forgotten etiquette practice: Traditionally, a woman was "Mrs. John Smith" while married, and "Mrs. Mary Smith" after her husband's death.

ReplyDeleteSo the choice to be identified by one's own name or one's husband's wasn't purely a matter of personal preference (or, in this instance, newspaper style); it actually signified something specific -- that one's husband had *died*.

Introducing Ms. as an honorific not only got around the need to identify whether or not a woman was married or unmarried, it also got around the need to identify whether she was married or widowed. Avoiding honorifics entirely (as most publications seem to do today) became another, simpler way to resolve this.

Also, McPherson and Prue likely were identified by their own names because many publications declined to use honorifics for African-Americans -- it was at one time a revolutionary gesture to refer to a married black woman as "Mrs. whoever" in print.

ReplyDelete